Since the early 1830’s, New Zealand had been promoted as a superb place for European Settlement. Even Hobart’s Colonial Times reported that half the people of Hobart Town are crazy to leave for the new Colony.

However, the stories of flesh-eating natives, warring tribes and events such as the “Boyd” massacre were still in the minds of many would be settlers. So, it was not until some sort of protection could be guaranteed would the majority of settlers start to migrate to New Zealand. Even then, it was only to certain areas of the islands.

The flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand, first flown in 1835. This was replaced by the British Union Jack in 1840 until that was itself replaced in 1900 by the New Zealand flag as we know it today.

The American’s and French had been showing a lot of interest in New Zealand, and the early English missionaries had by 1835 organised the United Tribes of New Zealand and declared themselves an independent country, which was even recognized by King William IV of Britain in 1836.

The following four years saw land sharks and settlement companies start to look for and purchase land from the local tribes. By late 1839, Captain William Hobson was given instructions to establish a British colony in New Zealand. On 6 February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed and New Zealand became part of the British Empire.

John’s life before his arrival in New Zealand is up for debate. In earlier pages, we have presented a number of options. One of my tasks was to try to find when he arrived in New Zealand. We can only assume, that a marriage may have occurred in Australia some time before his arrival and that John and a pregnant wife (Ann*?) set off for a new life in New Zealand.

John’s Arrival in New Zealand

By 1839, John had already sailed from Sydney with his first wife, Ann*, who, we understand is pregnant with their first child, perhaps on the brig Vision which made several voyages transporting settlers from Sydney to the Hokianga harbour at this time. The trip from Sydney to New Zealand has been estimated to take about one to two weeks (the fasted time recorded in this period was as quick as five days).

*It is worth a side note here which I cannot prove in any way other than place a good argument for the case of John James’ first wife’s name. It is my belief that John’s first wife’s name may have been Ann, or at least her middle name was Ann. The reason for this is twofold – a) the tradition of naming children after parents or family members, this would bring into play both Mary and Ann. b) the wet-nurse, and later John’s second wife is given an English name which happens to be “Black Ann” – a crude reference to her being the substitute for Mary Ann’s mother being a “White” Ann – all this is of course in no way proof.

Both delight and tragedy strike during the voyage, through either illness or the conditions on the journey. Ann goes into labour at sea and a baby girl is born – Mary Ann. At the same time, her mother Ann dies. We will never know the cause of her death but it could be assumed that giving birth to a child in those times was hard enough, let alone on a ship in the middle of the Tasman Sea.

Conditions could not have been worse, the chances of anyone on board being medically trained would have been slim, and any complications would not have been obvious. The fact that the baby survived may have been a miracle in itself. Ann is buried at sea and the ship continues its course.

In my search, no ships logs have been found with the name Stanaway on board. It appears that for the early arrivals, unless you purchased a ticket which entitled you to a cabin, then you were simply listed as one in a number of passengers in “steerage”. I have also looked for a burial at sea or any mention of this and have yet to find anything. It is possible that he may have acted as crew to earn his passage ,but again where ships have listed the crew the name Stanaway does not appear.

I am not certain if Hokianga was in fact the intended destination for the ship, but may have been the nearest port in which to get help for John and the newly born child. Russell was the main port for arriving vessels but this would have been a few more days sailing away. Again, I would have expected to find a ships log with this unscheduled stop recorded.

What we do know for certain is that Mary Ann Stanaway is born, and John’s wife has no records of having lived in New Zealand, and that John settles in the Hokianga Harbour area.

Kohukohu

Early settlement of the Hokianga was sparse, a small number lived near the mouth of the river, among them William Young at Koutu and Frederick Maning at Onoke, as well as Peter Monro and Robert Hardiman on the north side of the river.

Most Europeans, though, lived further up the river where the best timber was located.

These people were broadly divided into the sawyers living on the river’s upper tributaries, the remnants of Thomas McDonnell’s once-dominant timber operation at Horeke, White at Mata, a little down stream from Horeke, the Wesleyan missionaries at Mangungu, and the settlers and traders gathered around George Russell’s export base at Kohukohu.

The timber station at Kohukohu itself was owned by George Russell, who had been based there since 1837. From modest beginnings, Russell’s Kohukohu operation had, by the middle of the 1840s, become the single most important commercial centre on the river.

From the book “The Unknown Kaipara” by Brian Byrne, it is stated that by 1840 John is working for local businessman George Frederick Russell (1809-1855), in the timber trade shipping kauri spars and squared timber to London and other markets.

John’s Dilemma’s

In Barney Daniel’s writings, he suggests the dilemma John now found himself in, and it was critical for his first child – how does he feed this child? The family story says he needed a wet-nurse for the child and a young woman named Witaparene Minarapa was found.

Witaparene or Christine, (from William Stanaway’s, their first child’s Death certificate – Christine Stanaway is the stated name of his mother), was also known by the name “Black Ann”, at about the same time the Maori named John James, “Taniwe” (Refer to the handwritten tree from Ngati Stanaway’s records – Taniwe pronounced “Tan-a-way” – dropping the “S”).

As yet no records have been found of an official marriage between John and Witaparene, that is not to say they were not husband and wife in every way. Edward Markham who had spent almost nine months in the Hokianga in 1834 observed and recorded life in the upper Hokianga at that time (we could expect that it was no different six years later) , from his book New Zealand or Recollections of it, he writes;

All Sawyer’s live with Native women. In fact it is not safe to live in the country without a Chief’s daughter as a protection as they are always backed by their tribe and you are not robbed or molested in that case; they become useful and very much attached if used well, and will suffer incredible persecution for the men they live with.

He goes on to concede that the mother and father of the bride demanded gifts as the price of their daughters compliance.

At this time there was estimated to be approximately 2,000 European settlers in the entire country with around 100 of these living in the Hokianga area.

John, having settled down, soon had another issue – this time the raising of Mary Ann.

The Wesleyan mission station at Mangungu on the Hokianga Harbour, founded in 1828 and depicted in this drawing from 1838. – Alexander Turnbull Library

An issue presented to John, no doubt by the local Wesleyan Missionaries and their concerns with a European child being raised by natives.

Family stories have it that she was given to another European family to raise.

Two family’s, consisting already of a number of children, were possibilities for agreeing to take on Mary. The first were the Mariners, a family who John has a lot to do with both in Hokianga and later in Kaipara. We had heard only rumors that this family may have taken Mary in.

However, a review of the 1846 Clendon Census shows M Marriner – trader – w (Wife) and 4 children, which is consistent with the number of children they had at that time. (They had 5 children between 1838 and 1845 however the third son, Richard died in 1844). This would seem to discount the theory that the Marriners may have looked after Mary.

The second family we have looked at was the Hobbs. Rev John Hobbs, the local Wesleyan Minister, and his wife Jane, were living at Mangungu at this time. They are listed in the same 1846 Census with 9 children. We know that the Hobbs had a total of 10 children in all. Their sixth child, George, had died in 1838, and the tenth child was born after 1847, thus leaving them just 8 of their own children at the time of the census, not the 9 as listed – Mary may well have been the ninth.

Foot Note – John Hobbs registers the birth of Ngati Hemi (James Stanaway).

Foreman/Sawyer

The process of providing spars was hard graft as the entire process was highly labour intensive. We have to assume that John was involved in all aspects from providing spars, squaring timber and loading of these materials on ships for George Russell.

The collecting of spars for shipment took some time, so in between shipping some kauri was “squared” this involved, as you would expect, saw pits, long saws and a lot of sweat. The squaring of the timber simply involved trimming the sides, top and bottom of a log for easier loading and transporting. Some logs were cut into boards, but this was only for the local market, which consisted of the local missionaries, a few early settlers and the one or two ship builders.

The felling and shaping of spars was undertaken mainly by local Maori tribes who became the backbone of the early timber industry in New Zealand. As a result John’s work may have evolved into coordinating and loading of spars for shipment, as can be seen in Charles Hephy’s 1839 painting.

Charles Heaphy’s December 1839 painting shows a timber yard at Kohukohu, on the Hokianga Harbour. The ships are the Bolina (left) and Francis Spaight. A rowboat is hauling a raft of kauri spars to the ships. Kauri spars, used for ships’ masts, were one of New Zealand’s earliest exports. Alexander Turnbull Library

Charles Heaphy’s painting in 1839 of the loading of the spars at Kohukohu could well include our John as one of the workers loading spars.

The Treaty

By mid February 1840, Captain William Hobson had travelled from the Bay of Islands to Hokianga to seek more chief signatures on the Treaty.

A great gathering took place in Horeke where a haka of fifteen hundred men opened a massive feast to celebrate signing in the Hokianga. Around three thousand Māori feasted on pork, potatoes, rice, and sugar. Gifts of blankets and tobacco were distributed. John James may well have been at these celebrations.

Sketch by Richard Taylor, 1840, National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

The Timber Industry

We do have a document in which John appears, a reprint in the New Zealand Herald dated 12 March 1892.

It looks back in time to a proclamation issued on 30 October 1841 by the then Governor Hobson, prohibiting the cutting of kauri timber upon lands purchased by European residences in New Zealand, and making the same a felonious offence.

The local Hokianga residents put a petition to the Governor complaining about the proclamation and the effect it would cause. John Stanaway appears as one of the signatures of the partition, the article reads;

“PERILS OF THE TIMBER INDUSTRY IN THE OLDEN TIME.

It is rather amusing to find, in view of the history of the timber industry in Hokianga and elsewhere, that so far back as October 30, 1841, a proclamation was issued by the Governor prohibiting the cutting of kauri timber upon lands purchased by European residents in New Zealand, and making the same a felonious offence.

I saw at Mr. John Webster’s a copy of the petition of the Hokianga residents to Governor Hobson, in which the memorialists state that they had read with great concern the proclamation, and they complain of the ruinous effect it will have upon the settlers, and Hokianga in particular.

They plead that they had arrived before British sovereignty, and at a time when the New Zealanders were acknowledged an independent race and their flag saluted. Kauri was the only export and means of subsistence, and if the Act was enforced they would have to go out of the country, as they could not live if the timber trade were stopped, as it affected all classes.

The document is an interesting one as relating to the early history of the colony, where the kauri timber industry has flourished from that time to the present. The Governor, it may be said, yielded to the representations of the memorialists, and rescinded the proclamation.

Among the signatures to the petition are those of many old settlers :-Messrs. W. and J. Webster, William Young, Francis White, Henry Monro, Benjamin Gittos, John White, Thomas Poynton, George Nimmo, M. Marriner, G. F. Russell, Patrick Heath, J. Stanaway, Gundry, and Monk (father of Mr. Richard Monk).

The cutting down and export of kauri timber appears to have gone merrily on, for, in some other documents I inspected, our old friend, Dr. J. Logan Campbell, appears to have been in the Hokianga timber trade and loading up the Bellina with timber for home early in the forties.”

Two items are worth noting in this article – the first is that they are pleading the right to cut down the trees as they had settled in New Zealand before British sovereignty, when it was acknowledged as an “independent race.” This would imply, as he signed the document, that he settled in New Zealand before the signing of the Treaty in the beginning of 1840.

The second point to note is that John has crossed paths with a young John Logan Campbell. In 1841, Campbell was in the Hokianga again purchasing as many spars as he could in the barque Bellina for the British Admiralty. Then again in 1844, when Campbell bought timber from Russell.

During the second half of the 1840s Brown and Campbell sent three vessels to London carrying spars from Hokianga: the William Hyde in 1845, the Hope in 1847 and the Indian in 1848. (J.L. Campbell to father, 6 October 1846, 13 May 1847, Campbell Papers, MS 51, Box 3 item F14F, AWML; J. Webster to G.F. Russell, 12 November 1848, NZMS 4-19, AL; R.C.J. Stone, Young Logan Campbell, Auckland, 1982, p.134).

This acquaintance proves valuable to John later in life.

Birth’s, Death’s & Marriage

In 1843 John has a son, William, with Witaparene, and by 1844 they have a second son Ngaere. Assuming that they are born approximately 12 months apart, and the youngest is still a baby, would make the timing of his second marriage/relationship to Witaparene in approximately 1841 – 1842.

Then sometime approximately 1844-1845, Witaparene dies and John finds himself with two young children to look after.

At this point, we believe Witaparene’s half-sister, Henipapa Te Hokianga Minarapa or Jane (their son, Henare’s Death Certificate states his mother’s name as Jane), comes on the scene.

Whether to initially look after the children we do not know, but soon John and Henipapa are a couple. Like the relationship with Witaparene, we do not know what the arrangements were, if they married or if it was companionship, or even a business deal with her father.

1846 Clendon Census

In May 1846 the Resident Magistrate James Clendon completed his census of Hokianga’s European population, he counted 104 European residents (estimates of the local Maori population was about 3,600).

Resident Magistrate James Reddy Clendon about 1856 – Te Ara Collection

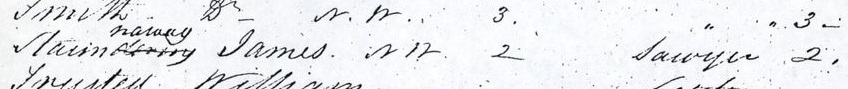

On page 8 the name – Stanaway James appears with a “N.W” (native wife) and two children. He is listed as a sawyer (one of fourteen sawyers in the area).

Interestingly in the Clendon 1846 census there was a division between those men who were described as ‘sawyers’, ‘labourers’ and ‘carpenters’, and those who were described as ‘settlers’, ‘traders’ and ‘merchants’.

“Gentlemen” such as Russell, the three Webster brothers, Maning, Marriner and Francis White, as well as McDonnell and William Young, were described as being among the latter group, while James Stanaway was clearly in the former group, which would suggest he was marked as working class.

Looking at the census we can see that Mary Ann is not back with her father – as mentioned earlier we suspect she was still living with the Hobbs family.

1846 Clendon Census – Stanaway James – NW – 2 children – Sawyer

Assuming this, the two children listed in the census would have to be William and Irahapeti (Elizabeth) (1844), (as Ngaere has been sent to live with his mother’s family in the Gisborne area).

The “native wife”, assuming Witaparene has died some time in 1844, would be wife number three, Henipapa. Note – She could well have been pregnant with John’s fifth child at the time of the 1846 census.

More Children

John and Henipapa go on to have a total of five children, 2 sons and 3 daughters – Irahapeti Rihi Tanap 1844, Ihapere (Isabella) 1847, Kataraina Te Rimi (Katherine or Kitty) 1848, Henare (Henry Joseph) 1850, and Ngati Hemi (James or Jimmy) 1852.

Henipapa’s mother was from a Waikato tribe but Henipapa was reportedly from the Te Rarawa tribe – who were from the north side of the Hokianga.

From the book “A White Tohunga” by P&G Kullberg – Page 40

He married a Maori woman of high rank, Henipapa Minarapa, of the Rarawa tribe, when he was working in the timber trade at Hokianga.

Rangiora

By October 1848, John has left the employment of George Russell and has moved to Rangiora in the “Narrows”, down river from Kohukohu and is now working for Mr Hastings Atkins (Refer “The Unknown Kaipara” by Brian Byren), where he may have been more involved in the unloading, loading and shipping of goods and timber for his new employer.

Rangiora was one of the most strategically important places on the river, the Narrows. Here the river was, as the name suggests, at its narrowest, but also its deepest, offering good anchorage for the ships that came up the river to Kohukohu to load timber and provisions for foreign ports.

Hastings Atkins – Auckland War Memorial Museum

Atkins was involved in the Hokianga timber trade throughout the 1840s and early 1850s. In 1850 and 1851, for example, he was granted a 12-month licence to cut timber on what had been Matthew Marriner’s old land claim at Rakaupara, near Kohukohu.

Shortly afterwards, however, he seems to have shifted his area of interest to Kaipara – likely due to the dominance of George Russell’s operation. (See Register of licences issued occupy crown land, depasture and cut timber, OLC 3/4, ANZW; Application for renewal of timber licence to Hastings Atkins, IA 1 50/2213, ANZW).

From the “The Unknown Kaipara” book it is said that John went to sea for a short while. John Campbell infers that John may have been the mate on the brig “Raven”.

Mangawhare – move to the Kaipara

Between 1850-52, John has relocated himself to Mangawhare in the upper reaches of the Kaipara (now part of Dargaville), following the movements of Mr Atkins, his employer, who had recently opened a new trading station there, and by all accounts was moving his main operation there. (Atkins starts a partnership with Brown Campbell & Co. and, in time, will finally sell his interest to them and leave New Zealand).

In 1852, John is mentioned assisting with loading of the spars on to the “William Hyde”.

A letter written by John Campbell on 9 November 1852, where he endorsed Atkins comments that;

It was a mind easier to have Stanaway’s services at Mangawhare.

This may have been the catalyst for John to be relocated to Mangawhare on a more permanent basis. Campbell later describes John as Atkins “Factotum” – a person having many diverse activities or responsibilities.

It is worth mentioning that Atkins did not reside at Mangawhare, but had placed Matthew Marriner there as Manager of the trading store in 1849 (refer page 19 – Early Northern Wairoa by John Stallworthy). Atkins had land all around the upper North Island including in Hokianga, Onehunga, Mt Eden and in the Kaipara.

It would appear that John was more than just any employee, not just physically loading and unloading, but perhaps piloting vessels up and down the Wairoa River and in and out of the Kaipara Harbour on behalf of Atkins.

With his work now having him passing in and out of the harbour, he would have increased his knowledge and made him by sheer number of times, the most experienced man on this stretch of water, far more than any other person. This may have led to the comments such as from the book “A White Tohunga” by P&G Kullberg – Page 40

Being a master mariner, John Stanaway, widely known as J.J., unofficially held the office of pilot from 1840 to 1855 and officially from 1855 to 1860…..

In August 1853 we have another letter from John Campbell to Atkins stating;

If G Stephenson cannot leave the Kaipara it may pay to send back Stanaway if you can possibly spare him as there is no-one in Auckland who knows anything about the Harbour.

Then again a month later Campbell describes John as Atkins “Overseer.” Could we assume that Marriner is looking after the trade and store and John is looking after the shipping interests for the absent Atkins (who is based in Auckland).

From this we have confirmation that by 1853 John is knowledgable about the harbour, so much so that John Campbell has requested him by name – we assume to pilot one of his vessels into the harbour. As a side note could we assume that a Mr Stephenson had a similar knowledge of the Kaipara bar?

We do have a number of shipping records which were published in the Daily Southern Cross between 1853 and 1854 stating Stanaway as the master of the Te Tere.

This vessel was co-owned by Atkins and Brown Campbell & Co., trading in the Hokianga and Kaipara perhaps into Auckland (Manukau Harbour/Onehunga).

Note – the shipping agent was in most if not all cases Brown Campbell & Co;

- 1853 Feb 5 – Te Tere 18 tons, Stanaway, for Kaipara via Hokianga.

- 1854 Feb.4 – Te Tere, 18 tons, Stanaway, from Kaipara.

- 1854 Feb. 5 – Te Tere, 18 tons, Stanaway, for Kaipara via Hokianga.

- 1854 Feb. 21 Te Tere, 18 tons, Stanaway, for Kaipara.

The exact date John had left the Hokianga is unknown, but by the early 1850’s he has definitely set up his home in the Kaipara.

I believe there is a link with John Logan Campbell, Jj appears to have crossed paths with him on a number of occasions, I am currently reading Poenamo (JLC’s memoirs) to see if JJ is mentioned at any stage -anyone have any confirmation of this?

LikeLike

need help with my family tree have got as far as Witaperene (black Ann) minarapa – JJ Stanaway then is mohi te hokaanga her father and harehura minarapa her mother ? or is mohi te hokaanga II her dad ? please help and has any one worked out if Mohi Tawhai and mohi te hokaanga are the same person ?

LikeLike

Clayton -I did a post last year based around some information put together by Joseph Patrick Stanaway and Tom Parore back in the 1930’s – see link

https://johnjamesstanaway.com/2016/10/18/mohi-te-hokaanga/

Then later edited by Patrick Stanaway – Joseph’s son, in the 1980’s – in this they believe that Mohi Tawhai and Mohi Te Hokaanga were one in the same person, and that he went by other names also.

We have not been able to get any further information than we have in the above post and what is in Tides of Time – it did not help that over this period Maori name rules changed 3 to 4 times (naming not same as European ‘rules’)

“Mohi” as I understand is Maori for Moses – that being the case Mohi would have been adopted after missionaries arrived – but he would have been born before the first missionaries arrived – Mohi Te Hokaanga may well mean Moses of Hokianga, Mohi Tawhai maybe the mane he took after being baptized (very common when converting to Christian faith) – it maybe that his original name was Tawhai and Mohi or Moses was added after this event.

We may never know – but I would assume that Joseph and Tom being closer to the date would have had better knowledge or at least 2nd hand information than we have now (5-6th hand information)

Greg

LikeLike

Kia ora. Where did you find the information for Henipapa? I’m looking to trace her ancestry if possible. Thank you.

LikeLike

Kia ora Kathryn,

The information I have on Henipapa has come from the Tides of Time – in the latest Revision 2013 a hand written tree was included (see Henipapa’s page and click on the thumbnail it will enlarge). This is from Ngati Hemi’s family records (a typed interpretation is underneath it). I am not in possession of the original but Wendy may be able to assist – you can contact her through the John James Stanaway Facebook page as she hosts this. She has also done some work on associated Hapu which may shed more light.

Also in the same revised editon of Tides of Time it states the Erina Samuels looked after her in her old age. We need to make contact with this branch of the family – hopefully this would help us make clear more of Henipapa’s life.

The rest is more of a comentary on that information – for example – two of her children it is told left their mother and swam across the river to live with their father (John) which tells us that the children where living with their mother on the opposite bank, and that also shows that John and Henipapa did not share a home together. (Why?)

My 3rd great gandmother was her half sister Witaparene and there is about as much information on her which is very frustrating. (Infact look at her page also as she has a simiar tree which may help, again this is from the latest version of Tides of Time).

If you do come across any additional of different information please share it.

Regards

Greg

LikeLike

Kia ora Greg,

Henipapa was my 3rd great grandmother, so we’re from the same generation just different lines! My grandfather gave his children a whakapapa linking Hone Hokaanga to Mohi Tawhai (chief of Nga Puhi during the late 1700s to 1800s). I’ve had a look at Mohi Tawhai’s whakapapa and don’t see Hone Hokaanga. Has anyone looked into the possibility of Henipapa (and maybe Witaparene) being whangai (adopted) by Mohi Tawhai? If Hone Hokaanga was intact the chief of Ngati Whatua at the same time as Mohi Tawhai was the chief of Nga Puhi, maybe fought against each other during the early 1800s when Ngati Whatua went up north. I think Ngati Whatua lost those battles to Nga Puhi. Maybe Hone Hokaanga died or gave up his children to the winning chief? I think this was a practice from what I’ve learned?

Cheers,

Kathryn

LikeLike

I have some handwritten notes from Patrick Stanaway dated 1982 in which he states that Hone Hokaanga and Mohi Tawhai are the same person. His father Joseph Patrick (son of Henare who was the son of JJ and Henipapa) prepared the chart written out in 1930 with these names on it. He was aided by Tom Parore who was the grandson of Parore Pouaka Te Awha a chief from the Kaihu/Dargaville area. According to Pat these and other names such as Hone Papa and Tawhai of Waima were aliases and the name of Mohi was taken when he was baptised by the missionaries in 1836. It is possible that Harihura and Wetekia were acquired on expeditions/raiding parties to the south. It seems to have been quite usual to take the wives or daughters of the chiefs who were defeated in battle.This may also explain why JJ was able to have a relationship with both Witaperene and Henipapa. I will email copies of the papers to Greg.

Regards

Colleen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Colleen – I will wait for the papers – have been busy over the last 3 weeks so have not been able to get back in to the research just yet

Greg

LikeLike

Kia ora Kathryn,

Thanks – It is worth a look into – at the moment I am trying to get the three generations history researched then posted on this site and am hoping people like yourself will add detail on their branches – I will send you an email off-line.

Greg

LikeLike

Awesome work you’re doing here Greg. I know from my own experience putting the updated book together, just how time you are dedicating to this. Well done and a big thank you. I am enjoying reading the site.

LikeLike

Hey – Thanks Wendy, I have been working on this for some time, but only posted this last week (adding page by page). I am making my way through all of JJ’s offspring, but it takes time. As I know your from the Henare Branch (and I am working my way through this at present) let me know if you have any more information on him and his children (I have just posted Annie Stanaway since your message). I will send you an email off line shortly.

Greg

LikeLike

Pingback: Recent Updates as of 05.10.2015 | Captain John James Stanaway 1813 – 1874

I am one of Pat Stanaway’s granddaughters. If possible, I would love a copy of the papers my grandfather gave to Colleen Stanaway.

Regards, Stephanie Wood

LikeLiked by 1 person

i am Jacinta daughter of David Stanaway.son of Joseph Patrick Stanaway son of Henare Joseph Stanaway. Before dad died he told me his great grandfathers mother Heniepapa was the last remaining member of a tribe from a maori battle fought in the waikato area ,she was about 4 years old found in the hollow of a tree her entire tribe had been wiped out ., she was taken to live with the northern tribe who had decimated her tribe. she was supposed to be the daughter of the maori chief from the waikato.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for you comment Jacinta, I will add it to Heniepapa’s page, I do recall someone else mentioning a similar account. Let me know if there is any more information you have on your branch of the tree.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi,

Where can I find information relating to George Nimmo?

LikeLike