The final option we have is a John Stanaway who was a “Waterman”, working we can assume on the Thames River. From the description records you will see later in this section John’s trade is given as “Waterman”.

A waterman is a river worker who transfers passengers across and along city centre rivers and estuaries in the United Kingdom. As well as in Britain itself, the term “watermen” was used to describe boatmen performing essentially similar duties on coastal waterways in the British colonies.

The watermen’s traditional open boats were known as wherries and had been used on the Thames since the 16th century or earlier. They were beamy clinker-built boats, often double-ended, painted green or red and with seating for passengers.

Wherries had pointed bows so that they could get close in to shore and let their passengers off without them getting their feet wet. Covers could be raised to protect the passengers from rain and sun. The Watermen’s Company tried to standardize these boats and ensure they were sound.

The waterman’s skiff was a later development of the wherry. It was a smaller craft with a transom or flat stern.

(From discriptions later shown in the Kaipara and Tokatoka sections, we will see that it is a skiff that John uses as his pilot vessel).

Conviction & Sentencing

From records we have John Stanaway was arrested and tried in the Kent Quarter Sessions.

The County of Kent is located on the south side of the Thames River to the East of Greater London area. It is worth noting that Dartford is at the western boundary of Kent – latter we reveal a letter John sent to Dartford, which gets returned.

The sessions were presided over by at least two Justices of the Peace (JPs) and were held quarterly in each county at Epiphany (December/January), Easter (April), Midsummer (July) and Michaelmas (October). The JPs also dealt with other disputes such as poor law disputes, settlement issues, bastardy cases, bankruptcy, planning, licensing and the transportation of criminals. Records from the session contain court rolls including the criminal trials, the indictment and juror lists and the minute and order books which will contain name indexes. The courts are referred to as quarters as the courts at the time only sat four times a year.

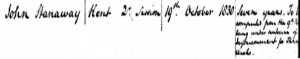

John Stanaway was sentenced on 19 October 1830, Kent Quarter 2nd Session, at the age of only 17, to seven years for housebreaking and stealing a pair of trousers. It read;

Seven years. To be completed from the 9th Nov being under sentence of Imprisonment for three weeks.

The three weeks to be served in prison (being from 19 October to 9 November) was for stealing a pair of trousers this he is to complete first (Refer to his record sheet below). The seven years will be for house breaking.

What is not clear is why he is sentenced in 1830 but is not transported until 1833. It may have been that he was considered too young to be transported.

The England and Wales Criminal Records of 1830 page 352 and 353 state;

County of Kent, Name John Stanaway, When Tried Michaelmas 1830, Crimes Larceny plus Convictions, Death (Blank), Transportation 7 years, Imprisonment 3 weeks.

TRANSPORTATION

We understand John was held on a ‘hulk’ before deportation.

He was given the Police convict number of 1671, and transported on the ship “Enchantress”. The “Enchantress” left Portsmouth sometime between 6 and 13 April 1833 and arrived in Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on 31 July 1833. This was a three and a half month journey.

A Brief History of Convict Transportation to Australia

Between 1803 and 1853 approximately 75,000 convicts served time in Van Diemen’s Land. Of these 67,000 were shipped from British and Irish ports and the remainder were either locally convicted, or transported from other British colonies. This represents about 45 percent of all convicts landed in Australia and 15-20 percent of all those transported within the British Empire in the period 1615-1920.

In the years to the ending of the Napoleonic Wars prisoners arrived in Van Diemen’s Land intermittently, as during times of warfare increased military recruitment resulted in lower rates of unemployment. The reverse was true in periods of peace where demobilisation appears to have created hardship, particularly in urban areas.

The first convicts shipped to Van Diemen’s Land were sent following the partial demobilisation of the army and navy during the short-lived treaty of Amiens in 1802. The next convict transport to arrive direct from Britain was not despatched until 1812, and it was only after the post-1815 general demobilisation of the British armed forces that Van Diemen’s Land became a regular port of call for convict ships.

As a result the number of serving convicts in Van Diemen’s Land rose from just over 400 in 1816, to a peak of over 30,000 in 1847. Thereafter numbers declined rapidly, especially following the cessation of transportation in 1852. By 1862 only just over a thousand serving convicts remained.

On arrival in the Derwent convicts were brought before a board headed by the Superintendent of the Prison Barracks, so that information about previous work experience could be elicited. The administration put a great deal of faith in the quality of this occupational data. Lt-Governor Arthur argued that, ‘The man perceives at once that the officer who is examining him does know something of his history; and not being quite conscious how much of it is known, he reveals, I should think, generally a very fair statement of his past life, apprehensive of being detected in stating what is untrue’.

As Arthur implied, the board cross-checked the statement of each convict with the information forwarded from the British Isles. This process was used to identify skilled workers and separate workers into trades. Thus shoemakers and tailors were categorised according to skill (can cut out or can’t) and by area of specialisation, for example: coat; boot; children’s. Special care was paid to the recording of agricultural skills – ability to plough, harrow, sow, mow, milk, thatch, shear, tend various types of livestock, break horses, cultivate hops, castrate lambs, treat scab, navigate ditches and even poach were all regularly listed.

Each convict was then stripped to the waist and any distinguishing features were put on file. In an era before fingerprinting and photography, this information was required for identification purposes. The process also had a psychological impact on convicts and was clearly designed to be demeaning. As the American political prisoner William Gates recalled, ‘such a minute description is obtained, that it is utterly hopeless for a prisoner to think of escaping from the infernal clutches of those petty tyrants, that hold such detestable sway in that prison land’.

Once disembarked, male convicts were marched to the Prison Barracks and females to the Cascade Female Factory. There they were kept for a short period while it was determined where they would be deployed.

Before 1840 the majority of prisoners were assigned to private individuals. Small numbers were retained to work at public sector tasks including working as clerks, flagellators, overseers, seamen, blacksmiths, masons, bricklayers and carpenters.

Contrary to popular perception, convict Van Diemen’s Land was anything but a vast gaol. Assigned convicts laboured under little or no restraint. Those who worked in the public sector were generally housed at night in secure accommodation; although as late as the mid-1820s it was not unusual for some skilled prisoners to rent rooms in town.

Convicts found in breach of the rules and regulations of the convict department could be brought before a magistrates’ bench. Punishments awarded varied from fines, cautions, floggings (of from 12 to 100 lashes) and sentences to the cells, tread-wheel and the public stocks. Sentences to road and chain gangs could also be awarded, although only a bench consisting of more than one magistrate could sentence a prisoner to a penal station or extend an existing sentence of punishment.

Despite the array of available sanctions, most masters stressed the importance of rewarding assigned servants, especially those with valuable skills, above the use of punishment. There is some evidence, however, that resort to punishment was more common at certain times of the calendar year, particularly during the harvest. This may have been due to a number of factors. Convicts, for example, may have chosen to play up at a time of the year when their skills were particularly in demand, hoping to increase the levels of incentives with which they were furnished. Alternatively, masters may have been tempted to push their charges harder in response to the dictates of the agricultural cycle.

Yet, despite popular perceptions of convict transportation, punishment regimes were a minority experience. In 1836 only 18 percent of male prisoners were deployed in road parties, chain gangs and penal stations, compared to 53 percent in assignment.

Criminal Records

Part of the process of transportation was a description of the convict was taken, a standard form was developed and in later years a new technology was used called photography. We now get our first description of John;

Name: STANAWAY John – Trade: Waterman – Height (without shoes): 5/7 – Age: 21 – Complexion: Fair – Head: Small – Hair: Reddish Brown – Whiskers: – – Visage: Long narrow – Forehead: Perpendicular – Eyebrows: Reddish – Eyes: Grey – Nose: Sharp – Mouth: Small – Chin: Long – Remarks: Thickly pock pitted, E.W ins. left arm.

This description could be the key to this option, unfortunately, we can only compare this description of a young John Stanaway with only three pictures of a much older John James Stanaway, of which are only black and white. If only we could see his left arm!

Some have suggested that the remarks section indicates that he is “missing his left arm”, this I believe is not what this says – all be it that I have yet to determine what it does say, no doubt “E.W” is an abbreviation for something. (Note – The founders and Survivors website http://foundersandsurvivors.org/pubsearch/convict/chain/c31a31400023 – indicates it state E.W ins (inside) left arm).

I have two issues with this the first being that I am sure the courts would not transport a one armed convict, as he would be of little use, especially for the cost of sending him. Secondly and more importantly, he would have had a hard time working as a “Waterman” (rowing a boat) with one arm!

Another item of note is that it has “NR High Wycomb” – this indicates his place of birth was “near High Wycomb”. This does not tie up with Ngaere Stanaway’s notes, where it states John was from Camberwell, it is 60 miles away. Then however we see he is convicted at the Kent Quarter which is close to Camberwell. A reason may be that he was born near High Wycomb but grew up and lived his early life, before conviction, in Camberwell. (Note the 1841 UK Census shows no Stanaway’s in High Wycomb).

According to the 1833 Convict Muster (as at 31st December) he was assigned to the marine department. Not surprising as is occupation was listed as a “Waterman”.

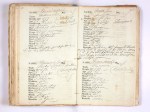

Musters were essentially “Head Counts” and used to monitor the prisoners and used to anticipate the supply and demand requirements on the Government stores. Musters were not done each year, however the years John should appear on this list would be 1833, 1835, 1836, 1837 and 1841 (We have managed to get copies of only 1833, 1835 and 1841).

We have one more document which gives his convict number – 1671, his name – Stanaway John, his job – waterman, and the department he was with – Marine Department.

Watermen were used in Van Diemen’s Land, on the River Derwent around Hobart and the River Tamar around Launceston. Regular ferry services across the Derwent existed by 1810. By the 1830s these ferrymen were known as “watermen”. The heyday of Hobart Town’s watermen was from the 1840s to the mid-1850s. They were held to be distinct from other categories of maritime workers such as the “boatmen”, “craftsmen” or “bargemen” who operated sailing vessels in the river trade, and those men operating on the steam ferries and river steamers that also operated out of the port.

By the 1835 Convict Muster (based as at 31st December) we see he has been moved to Public Works – likely to be in the Marine Department. (Refer to Public Works or Public Sector Works – refer to A Brief History of Convict Transportation to Australia).

Individual records were kept on each convict, these were complete records including their number, name, charges, date convicted, date and ship transported on, health, and records of offences which serving his sentence. His conduct register reads as follows;

1671 – (Prisoner number) / Stanaway John- (Name) / Enchantress – (Transport Ship) / 31st July 1833 – (Date transported) / Kent 2nd Session 19th October 1830 (Sentencing Date) / To be completed from 9 Nov being under sentence of imprisonment 3 weeks

Transported for Felony / Gaol Department – Orderly / Health Department – Good / Stated this offence – Housebreaking had on two indictments. One for taking a pair of trousers – 3 weeks imprisonment / Singles Surgeons Department – Healthy

- March 7, 1834 – Boats Crew, misconduct

- March 24, 1834 – Watchman, Neglect of duty

- April 6, 1835 – Marine Department. In a public house on a Sunday – punishment was 10 days on the “Twheel” (or tread-wheel)

- March 15, 1836 Marine Department. Drunk, admonished.

He (possibly) then appears in two of Hobart’s papers (Colonial Times and The Hobart Town Courier) in April 1838, (note – this does not appear on the above records so may not be our Stanaway) the Colonial Times states;

James Stannaway, employed under the surveillance of the Port Officer, as Deputy Water Bailiff, and hired servant to the Crown, as a warning, to all Government Officers, Superintendents, Chief and Assistant Police Magistrates,. &c, all, (excepting His Excellency), not to leave their duty, or travel up the country without leave, was ordered three days to the tread-wheel, for leaving his hired service.; The defendant admitted: he was absent two days, because he could not agree with the Water Bailiff Mr. Gunn’s roundabout will be fully occupied, if this System is followed up.

He is now as stated the Deputy Water Bailiff – similar to a fisheries inspector in today’s language.

John Stanaway is mentioned in The Hobart Town Courier dated 3 November 1837 which reads;

The period for which the undermentioned persons were transported, expiring at the date placed after their respective names, certificates of their freedom may be obtained then, or at any subsequent period, upon application at the Muster Master’s Office, Hobart town, or at that of a Police Magistrate in the interior:

John Mason 18th November 1837, Currency Lass ; Henry Andrews 26th do, Henry Hulkes 25th do, John Stennard do, William Stone do William Sidders alias Deverson do, Thomas Strood 26th do, Eliza ; James King do, Eng. land; John Stannaway 9th do, Enchantress; David Ross 10th do, Gilmore; Rich. Frederick 21st do, Larkins; Margaret Begrie, 15th do, Ann Phillips or Welch 10th do, Priscilla Wright or Fraser do, Mary; John Mallon 27th do, Science.

The official records finally show John in the Convict Muster record from the end of 1841, which states “Free by Servitude” – when a convict has served the period of their sentence they therefore became free – they were recorded as being free by servitude. – The title of this list states “Van Diemen’s Land – Return of Male and Female Convicts showing their distribution throughout the Colony on the 31st December 1841.”

We have him in records stating that he was then in the Hokianga area, New Zealand pre 1840.

Maybe Not “poe pitted” but pock pitted. Pock marks, ie pockmark ˈpɒkmɑːk/ noun plural noun: pock-marks

1. a pitted scar or mark on the skin left by a pustule or spot. “the only possible reason for the thickness of the make-up was the pockmarks underneath”

LikeLike

I think your correct – I will make the adjustment – also looking at the way the writer does their “K’s” indicates Pock

Thanks Polli

LikeLike

I recall reading somewhere that the remark about E W on his left arm related to a tattoo.

LikeLike

I contacted the TIRS and this is their reply…..

“High Wycomb would be the place where John was born. I suspect the E.W. may be initials on his left arm but I cannot be certain.”

The Port Arthur Historic Site offers a transcription service. If you would like to contact them here is the link: http://portarthur.org.au/research/research-enquiry-service/

Regards

Margaret Harman

Librarian

Tasmanian Information and Research Service

91 Murray Street

Hobart TAS 7000

Therefore it doesn’t seem to fit with John James as he was born in Surrey.

LikeLike

Thanks Sue,

I was not sure if High Wycomb was where he was held before deportation (have not got any details on any prison there), or the name of a hulk again where he was imprisoned (I have not found a hulk with that name). As you see he was convicted when he was 17-18 but then deported when he was 21. (Refer his prisoner log – sentanced in 1830 and deported in 1833 it has this 3 year gap!)

I do not know if they had a rule of deporting prisoners until they were a certain age – unless he had to serve 3 years not 3 weeks in prison before deportation for the larceny offence.

I am sure the trial and the deported John Stanaway are one in the same (refer his record sheet) it remains a question whether he is the same John James Stanaway who came to NZ, he may not be the same John Stanaway born in Camberwell!

I have left the Camberwell John Stanaway as the starting point as it is what is written on Ngati Hemi’s Family tree notes – which have generally been accepted as correct – we just do not know how he got to New Zealand – hence the options.

LikeLike

My Dad used to say when I was a kid in the early 1950’s that there were Stanaways in Tasmania who were not related. He alo sanid there were Stanaways in Dunedin similarly not related. I have never since heard of any from Dunedin.

The legend in our family I guess promoted by my Dad Leo Joseph at the time about JJ was the “genleman story” as outlined in that section. Interestingly my Dad never told us of our Maori hertage. That was left to my Nana (Ethel McCabe) who told my mother about it q when I was at University.. Also interesting was that Nana said that Dad could speak Te Reo Maori when he was a kid before age 5 because of all his playmate at Ruawai where he was born. I have heard that kids used to get whacked for speaking Maori at school in those days. He certainly never spoke any in my hearing. My cousin Ron Stanaway has a full record which he has given to me of the Cp JJ “Mutiny on the “Harmony”” story.

Kerry Joseph Stanaway Great Great Grandson of Capt JJ via Henipapa, Henare, Joseph Patrick and Leo Joseph

LikeLike

Thanks for the comments Kerry. My Great x2 grand father was Henare’s older half brother William. Both he and his wife were half casts making the children also half casts. I have to assume that William and his wife both spoke Te Reo, but perhaps not as well as Henare (we know Henare is used or becomes an interpreter later in life). This makes some sense as William after his mother died lived with JJ, so would have had spoken English more from an early age and if Henare and his sister did spend their early years with their mother across the river would mean they would have had a better grounding in Te Reo.

As for William’s children we have little knowledge if they spoke Te Reo, William’s great grandchildren in our branch did not speak any Te Reo the same for the next 2 following generations, my children now learn Te Reo at school as part of the school program.

There were a number of Stanaway’s in Australia about the same time JJ may have passed through there, if we have his family from England correct, his brother did live in Australia for a few years and married there before returning to the US where the rest of the family moved to.

There are Stanaway’s in Dunedin who are not related (but there are some their who are – from your branch – I think 2 of Henare’s sons moved there I think – check out their pages).

There was another Stanaway family who settled in Wellington early on but in a flash flood in the 1850’s most of the family were washed away to their deaths, house and all.

LikeLike

The abbreviation ins. could be inscribed as in a tattoo. Whence the mark E.W. could be a woman he took a fancy to.

LikeLike