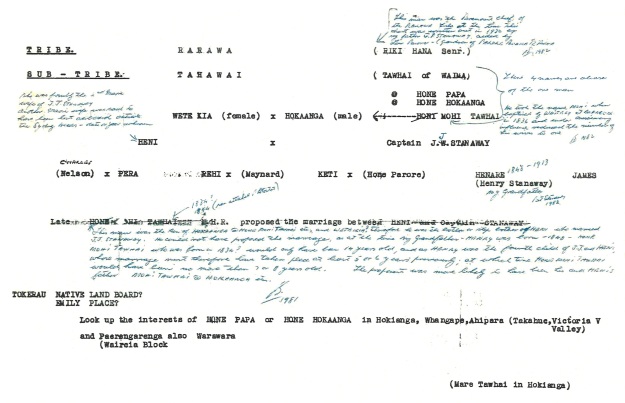

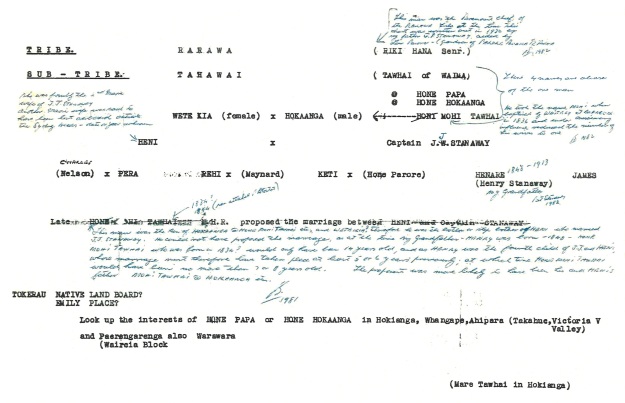

I have received a document written in about 1930 with handwritten notes added in 1981.

Joseph Patrick Stanaway (son of Henare who was the son of John James and Henipapa) prepared the chart showing Henipapa and JJ Stanaway and their children. Joseph was aided by Tom Parore who was the grandson of Parore Pouaka Te Awha a chief from the Kaihu/Dargaville area.

In 1982, Patrick Stanaway, son of Joseph, added some hand written notes in which he states that Hone Hokaanga and Mohi Tawhai are one in the same person. He also corrects part of the original document where there was confusion between Mohi Tawhai and Mohi Hone Tawhai, his son.

The chart shows that Wetekia was from the tribe Rarawa, sub-tribe Tahawai, and she married Hokaanga, of Ngapuhi.

According to Pat Stanaway the name Hokaanga is one of many names given to the same Chief – others such as Hone Papa and Tawhai of Waima were aliases and the name of Mohi (or Moses) was taken when he was baptised by the missionaries in 1836.

If this is the case then Mohi Te Hokaanga and Mohi Tawhai are one in the same person. Could it be “Mohi of Hokianga”?

The document in question

The hand written notes from Patrick Stanaway written in 1982 read as follow (clockwise from top of page);

Note under Riki Hana Snr. – This man was the paramount chief of the Rarawa tribe at the time this chart was written out in 1930 by my father J.P Stanaway aided by Tom Parore, grandson of Parore Pouaka Te Awha. – No comment on this note

These 4 names are aliases of the one man. – This relates to the key point of this discussion, is this statement correct, are they one in the same person?

He took the name Mohi when Baptised by Whitely _________ in 1836 and under missionary influence reduced the number of his wives to one. – This statement is correct and ties in with historical documents

Note under Henry Stanaway – My Grandfather – This statement is correct

Note under Hone Mohi Tawhai – This man was the son of Hokaanga @ Hone Mohi Tawhai etc, and Wetekia, therefore he was the brother or step brother of Heni who married J.J. Stanaway. He could not have proposed the marriage, as at the time my Grandfather, Henry was born – 1848 – Hone Mohi Tawhai who was born in 1834? Would only have been 14 years old, and as Henry was the fourth child of J.J and Heni whose marriage must therefore have taken place at least 5 or 6 years previously, at which time Hone Mohi Tawhai would have been no more than 7 or 8 years old. The proposer was more likely to have been his and Heni’s father Mohi Tawhai @ Hokaanga etc. – This statement is correct. It is correcting the error of confusing Hone Mohi and his father Mohi.

Note on Heni – She was formally the 2nd Maori wife of J.J Stanaway. Another Maori wife was said to have been lost overboard outside the Sydney Heads – date or year unknown.

This may either be the fate of Witaparene – which may explain her disappearance or it is getting mixed up with the story of J.J Stanaway’s first wife we have named Ann. This needs further investigation.

Note – we need to search the Wesleyan Historical documents of Hokianga, this may contain the marriages of J.J. Stanaway to both Witaparene and Henipapa

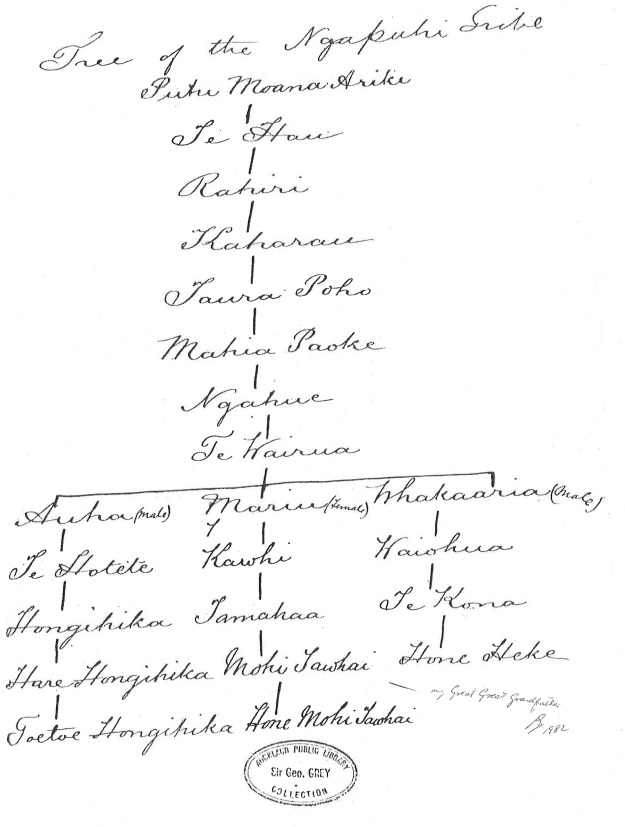

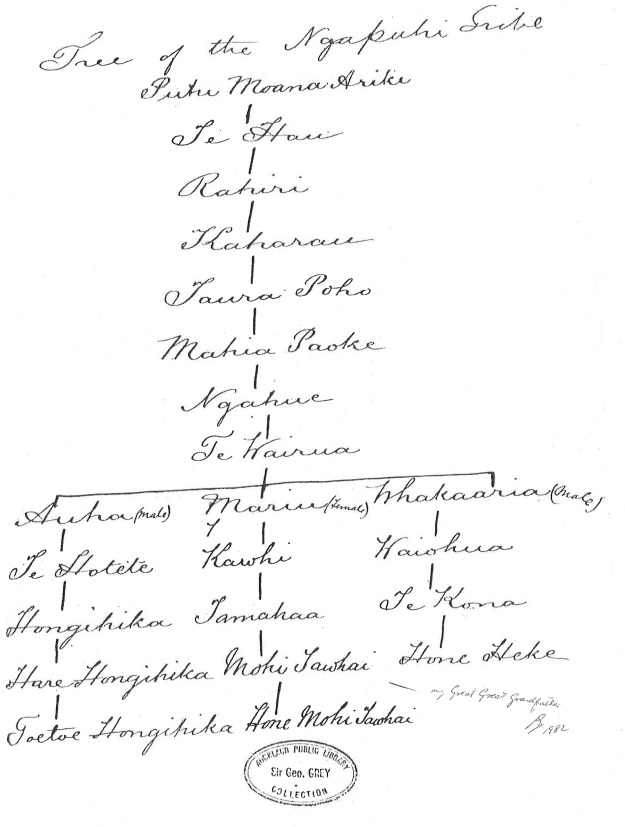

A second document I have received is from the Auckland Public Library, and part of the Sir George Grey Collection. It is the Tree of the Ngapuhi Tribe, had written with a note added by Pat Stanaway in about 1981. It shows the relationship with Hone Heke.

Mohi Tawhai (about 1793 – 1875)

Mohi was a very influential chief of the Mahurehure hapu of Ngāpuhi, residing at Waima.

The name Mohi Tawhai often gets confused or mistaken for his son who was Hone Mohi Tawhai (1827-1894) as can be seen originally typed in the chart. (Refer separate notes on Hone).

Mohi was a very influential chief of the Mahure hapu of Ngapuhi, residing at Waima (on the south side of Hokianga Harbour just south of Rawene).

Authors Note – Working backwards from the 1818 siege where he must have been at least mid-twenties would put his birth about +/-1793

Mohi – Maori Warrior Chief

He bore many scars and at the siege of Tapuinikau (1818) had his head split by a rock.

He was one of the Ngapuhi leaders in the expedition to Cook Strait (1819-20).

Among the Maoris certain warriors were noted for combining great personal strength and prowess with unusual swiftness of foot. When one of these toa (braves) was pursuing a routed party of the enemy, it was customary for him not to waste his strength in many blows, but to give one sharp disabling blow to a flying foeman, and leave him to be despatched by those coming on behind. One of the most celebrated of these fleet toa was the elder Mohi Tawhai of Hokianga, who had accompanied Hongi on his terrible and bloodthirsty raid on the South.

Mohi was said to have slain one hundred and fifty men with his single arm in one day. On one occasion as Mohi dashed along after the fugitives, he killed until his wearied hand could not be lifted. At this moment a very powerful native turned on him and with a greenstone adze struck at Mohi’s head. Mohi was quite unable to ward off the blow, which split his skull completely open. The wound healed, but left a very considerable depression in the skull, so that afterwards when the old man was sitting in the rain a little puddle of water could be seen standing on the head.

The arrival of the Wesleyan missionaries in the Hokianga had a profound effect on Mohi.

In 1836, he was baptised by Rev. Whiteley at Mangungu, at which time he took the name “Mohi” (Moses). Under missionary influence he reduced the number of wives to one. He was a staunch Christian, loyal to the Wesleyan missionaries.

Thereafter he was a preacher, led a good Christian life, and was a constant defender of the peace.

From the WHS Journal 1999 publication #69 page 33, we have the following account of Mohi as recalled by Hannah White the daughter of Rev. William White, Wesleyan Missionary;

There was an old chief, Moses Tawhai, a great warrior in whom we children took much interest. In fighting he had had his head split, and it made a deep cleft. Now, Maori chiefs were not supposed to have their heads touched by anybody, but Moses Tawhai, one day in our house, laid his head on our table and said, “Now children, come and each put your hand into the hole.” We did so, and we could lay our fingers in the slit.

It is at this point we become more interested in Mohi. It is about this time (1839) that J.J Stanaway has arrived in New Zealand. If the chart is correct then Mohi had daughters from different wives (Harehura and Wetekia), who he encouraged to marry a European.

Many Wives and Children

We know that Mohi had a number wives and children, how he came to have many wives could be one or a number of the following scenarios.

It could be that Harehura (Witaparene’s mother) and Wetekia (Henipapa’s mother) were arranged marriages to form strategic alliances with other tribes.

It is also possible that Harehura and Wetekia were acquired on expeditions or raiding parties to the south and north.

Both these options were quite normal in Maori culture at that time.

A further option could be that they may have been the wives or daughters of the chiefs who were defeated in battle, who he then took as his own.

The original typed notes states that Mohi proposed the marriage between Henipapa and J.J. Stanaway. This would have been after the death of Witaparene. We do not have any information on the roll he may have played in the union of Witaparene and J.J. Stanaway.

Patrick’s notes state that Witaparene was lost at sea outside the Sydney Heads, we are uncertain if this is perhaps some confusion with the loss of J.J. Stanaway’s first wife who we understand died at sea, or if it is in fact the fate of Witaparene, it could explain her disappearance.

The Treaty

Mohi signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Mangungu on 12 February 1840. (Waitangi Signatory number 145). He spoke before signing – from the Book “The Treaty of Waitangi and How New Zealand Became a British Colony by TL Buick.”;

“How do you do Mr Governor? All we think is that you have come to deceive us. The Pakehas tell us so, and we believe what they say.”

When all the speeches were ended Taonui and Mohi Tawhai signed the Treaty. (For those eagle eyed family history buffs out there will also remember the name Te Taonui being the grandfather of Susan Anderson – William Stanaway’s wife).

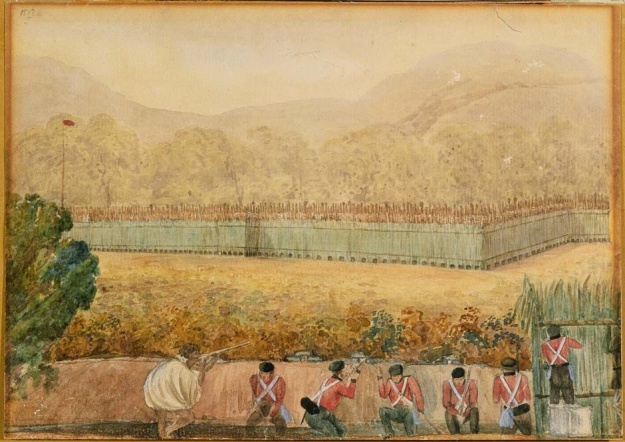

The Northern Wars

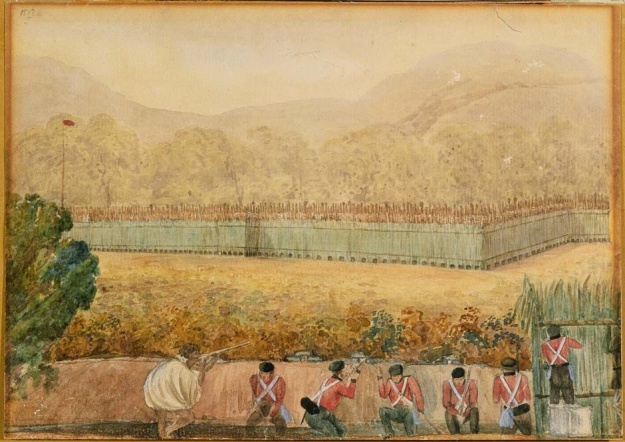

In the Northern Wars (Heke’s War 1845-46), Tawhai sided with Nene (Note Te Taonui also fought alongside Nene) against Heke. He distinguished himself in action at Ōhaeawai (June 1845) and strongly upbraided Colonel Despard for his decision to retire. At Ruapekapeka he built an advanced stockade 1,200 yards from the pa and with Nene, occupied open land 800 yards in front. When Despard ordered a premature assault he stood in the road to prevent the soldiers going to their death. In spite of their differences of opinion Despard considered him a very active and gallant soldier.

Ohaeawai Pa, 1845 – Cyprian Bridge, Alexander Turnbull Library.

He slept several nights in Pomare’s pa to prevent fighting.

Later Life

Tawhai was for many years an assessor and was very highly respected as one of the most learned men in the north. He was a friend of Governor Grey.

Mohi lived to extreme old age, probably to considerably over 80, but did not suffer from any brain-trouble.

He was killed (14 March 1875) by a fall from a horse while returning from church at Waima.

From the Wāka Maori, Volume 11, Issue 7, 6 April 1875, Page 78 we read the following of the death of Mohi;

To the Editor of the Wāka Maori. Waima, Hokianga,

March 14, 1875.

Friend,

I write this to inform you of the death of our father, Mohi Tawhai—a distinguished chief of Ngapuhi—which occurred on Sunday the 14th of March instant. He had been to church, and, after the morning service had been concluded, at 2 o’clock p.m., he mounted his horse (to return). The horse shied and he fell to the ground, completely breaking his neck.

When the people reached him he was quite dead, so that he uttered no word of counsel to us or to the tribe. He was an aged man, and a chief of great power and influence in Maori affairs, and also in Pakeha matters —in upholding Christianity and in suppressing crime in the land. He was energetic and powerful in promoting the welfare of the tribes. His hand was strong to grapple with difficulties, and to overcome them by the power of his right arm.

For a period of over 36 years he had been a professor of Christianity and a supporter of the Faith among his people, and also of the laws of the Government. He sought satisfaction for the blood of the Pakeha shed in the war of Hone Heke at the Bay of Islands, Ngapuhi (i.e., he took the side of the Government).

From that time he has been the friend of the Pakeha and of the Maori also. We are in great trouble on account of his death, which came so unexpectedly.

From yours in love,

Mohi Tawhai Wikitahi.

We believe this is written by Mohi’s son Hone Mohi Tawhai.

The Daily Southern Cross had the following insert in its paper on 30 March 1875;

HOKIANGA DEATH OF MOHI TAWHAI.

Sunday, the 14th, which was ushered in so bright and peacefully, was suddenly rendered a day of sorrow and gloom by the death of our esteemed and lamented native chief, Mohi Tawhai, the principal chief of Ngāpuhi, excepting Rangatira, who is about equal in rank. He had just been worshipping with his people, as, he regularly did, when he was able, and was mounting his horse when, through dizziness or other weakness, he lost his balance, and, falling on his head, dislocated his neck, as he never moved or spoke afterwards. A number of natives who were sitting outside the schoolhouse (where Divine Service is held) saw him fall, and immediately ran to his help, but too late. Mrs Rowse kindly rendered all the aid she could, as did Mr Barrett and some natives, not knowing at the time the extent of his injuries but it was soon evident, though we were unwilling to believe it, that life had fled, and that the once brave and powerful chief was no more.

He, whose presence in the fight inspired his companions with courage and filled his foes with dread, had become weak as an infant. Though his conduct, as well as his judgment, was not always faultless, yet all will acknowledge that he was ever a devoted subject of our Queen, a true friend of the Pakeha, and, we sincerely believe, a real Christian, one who eschewed vice in himself and discountenanced it in others.

We have looked around for one to fill the gap his death has made, but we cannot find one. True, there are one or two secondary chiefs who are respected by the tribes here, but they have not the influence that Mohi Tawhai or Adam Clark had.

The natives suffered a great loss in the death of the latter as well as Mohi’s death, they need someone to lead and control them. Formerly they were a pattern of industry and sobriety, but many of the young men are becoming the slaves of drink, and waste their time and money in card-playing.………….

Mohi Tawhai was buried on Thursday last, the 18th. On Monday and Tuesday there was a continual tangi, one large party had scarcely ceased their wailing when another would arrive. One celebrated gentleman here surpassed them all in his lamentation for old Mohi Tawhai, at least so the natives acknowledge.

We, new chums, are not up to that sort of thing, but one could hardly repress a tear as his remains were committed to the dust. There was true sorrow, we believe, in the breasts of some who stood around the grave, as the Rev. W. Rowse read the words in Maori “Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, etc. We were glad to see a disposition on the part of our most respected Pakeha residents to do honour to the late chief, among whom we noticed Judges Manning and Monro, Mr. Stunner, Mr. Yarborough, Mr. Frazer, and other gentlemen. A goodly number of natives followed his remains, which were interred in a lovely spot, but very difficult to ascend, the site of an old Pa. Judge Manning bade a last farewell in the name of the Pakeha’s present, giving it in Maori, and in which we would all have united if we had spoken as we felt. It is a comfortable thought to his tribe that he was buried in the sure and certain hope of a joyful resurrection to eternal life.

Another Mohi Tawhai

There is another Mohi Tawhai – this Mohi was of Manotahi in South Taranaki. He was captured with others by Ngapuhi and taken as prisoners to Hokianga. This Mohi was for some time a slave of a chief of Mangamuka. Mohi and his master later became Christians and Mohi was released. Later, he and eighteen other captives set out to preach to their own people at South Taranaki.

Hōne Mohi Tāwhai (1827/8-1894)

Ngapuhi leader, politician

This biography was written by Ranginui J. Walker and was first published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Volume 2, 1993

Hone Mohi Tawhai was the son of Mohi Tawhai and his wife, Rawinia Hine-i-koaia (also known as Harata). His father belonged to Te Mahurehure, a hapu of the Ngapuhi confederation, and the family was also connected with Te Whanau Puku. Te Mahurehure held the territory of Waima in Hokianga, and it was probably there that Hone Mohi Tawhai was born in 1827 or 1828. He was about 12 years of age when his father signed the Treaty of Waitangi at Hokianga on 12 February 1840. Little is known of his early life, but it is likely that he attended a local mission school and was associated with the Wesleyan missionaries in the area. His name, Hone Mohi (John Moses), is probably a baptismal name.

Tawhai assumed the responsibilities of leadership early in life. When the official runanga at Waimate North (established under Sir George Grey’s runanga system) became defunct in 1865, he kept an informal one functioning in Hokianga. He was appointed as an assessor to the Native Land Court in the north and influenced the people at Waimate North to co-operate peacefully with the court. He became highly regarded, and in 1867 was recommended by the resident magistrate E. M. Williams to the government for commendation for negotiating peace during an inter-tribal conflict that had led to blows. When quarrels again broke out over land at Otaua in 1882, the resident magistrate Spencer von Stürmer acknowledged the part played by Tawhai in preventing bloodshed.

By 1876, however, Tawhai had become disillusioned with the Native Land Court. The expense of getting a Crown grant, including survey and court costs, was seen as an unnecessary financial imposition. In June, in a letter to the council of Tuhourangi at Rotorua, he indicated that Ngapuhi wanted the court abolished and the law changed so that land which had not been put through the court would remain under ancestral title. Nevertheless, he represented his hapu before the court, and conducted their cases for major claims such as the Waima block in 1885 and 1886.

Tawhai was the member of the House of Representatives for Northern Maori from 1879 to 1884. In January 1880 he was appointed to sit on the West Coast Royal Commission to inquire into Maori claims against land confiscations in Taranaki and the detention of prisoners who resisted the government survey. Initially, he did not want to take his place, but he was persuaded by the minister for native affairs on the grounds that he was impartial, not having been involved in the wars.

Before the commission sat, Tawhai voted against the Maori Prisoners Detention Bill of 1880 because it had not been printed in Maori and was being rushed through the House: he refused to support ‘blindfold’ a measure that was hurriedly presented. He also criticised the shipping of Maori prisoners from Taranaki to gaols in Dunedin and Hokitika as a move to get rid of them; he felt they would perish in the colder climate of the South Island. Tawhai then declined to sit on the commission with William Fox and Francis Dillon Bell, because the former was implicated in the Taranaki confiscations and the latter in the purchase at Waitara.

Although he had little formal education, Tawhai was naturally talented and made a strong contribution to parliamentary debates on a wide range of issues. He was independent-minded and claimed the right to vote as he pleased. He was particularly critical of the government’s borrowing from Britain to pay for a war he regarded as aimed at destroying the people at Waitara. He opposed the introduction of legislation designed to alienate Maori land, believing that the proceeds of land sales would be used to help defray interest on the loans. He also criticised the expenditure of more than £20 million borrowed for public works in the 1860s and 1870s, objecting to the imposition of a property tax on his constituents to pay for the loans when none of the money had benefited the north. He claimed that other districts received benefits in the form of railways and public works but Hokianga had received nothing. He warned that if the government persisted in taxing Maori land it would need an army of 24,000 to enforce the taxes. Tawhai voted against the Crown and Native Lands Rating Bill 1880 on the grounds that taxing Maori land was another step towards its alienation.

In 1881 and 1882 Tawhai and Henare Tomoana were responsible for the Native Committees Empowering Bill; it provided for committees which would replace the Native Land Court and determine titles more rapidly and honestly. The government sponsored a modified version the following year, but it was not a success. In 1881 Tawhai accused the government of betraying its duty to protect the Maori and ward off such evils as might threaten them; instead, it had oppressed them. Because the Legislative Council had produced bills which he approved of, such as the Native Lands Frauds Prevention Bill and the Native Succession Bill, he thought that the House of Representatives should be abolished and the council retained. When suggestions were made in the debate on the Representation Bill that the Maori seats should be abolished, Tawhai defended them. He argued that the right to representation emanated from Queen Victoria through the Treaty of Waitangi; if members could show him an act or law which had abolished the treaty, then he would say no more.

As an advocate of Maori rights, Tawhai argued that laws not made in accordance with the Treaty of Waitangi were the cause of ill-feeling between Maori and Pakeha. He believed that Maori aspirations could be achieved by working through Parliament. Accordingly, in the early 1880s he remained aloof from the movement advocating full implementation of the treaty. Instead, he urged Parliament not to make laws from which evil effects flowed. But by 1890, when it became clear that Parliament was not interested in following Tawhai’s advice on the treaty, his political views shifted, and he began to respond to Maori movements outside Parliament. In May 1890, he chaired a meeting of the Northland tribes at Omanaia, a place that was spiritually significant to the followers of the mystic Aperahama Taonui, who had been prominent in the treaty movement of the early 1880s. This meeting established an organisational structure that culminated in the formation of the first Maori parliament at Waitangi in April 1892. When there was conflict in the north in the 1890s over the controversial dog tax, Tawhai continued to urge moderation and adherence to the rule of law, advising his people that the proper course was to petition Parliament to change the law.

Tawhai had reservations about the writing of Maori history by Pakeha. Nevertheless, he corresponded with the ethnographer Stephenson Percy Smith, supplying him with information on Maori origins in Rangiatea, the Hawaiki origin of the names Waima-Tuhirangi and Moehau, the ancestral canoe Omamari, the descent lines of Ngapuhi from Tumutumuwhenua and Nukutawhiti, and Hongi Hika. Tawhai also intended to write the history of Hongi Hika, but the protracted illnesses which ended his life prevented him from undertaking this work.

Hone Mohi Tawhai died on 31 July 1894. He and his wife, Makere Maraea, had at least two children: Hone Takerei Tawhai and Kereama Tawhai. Kereama died in 1885 at the age of 21, while studying law with the Auckland firm of Whitaker and Russell.